Sancho Describes the Gordon Riots

Ignatius Sancho's shop was just a few hundred yards from the Houses of Parliament and so he may have had a ring-side view of the Gordon Riots of June 1780. The riots began with Lord George Gordon's protest against an act for a small measure of toleration for Catholics, an act deeply resented by many in Protestant England. Soon, however, the protest got out of control as 'the mob'—the ordinary working people—vented their anger at the hardships of their lives. Political protest turned into anarchy as groups of Londoners broke windows, burned down the homes and chapels of Catholics, and finally set free the inmates of Newgate, London's main prison. Along the way over a thousand people died. Hundreds were burned to death in an inferno after a distillery on High Holborn was set on fire. Fire-fighters mistakenly pumped raw alcohol onto the flames, thinking it was water. After more than a week the army finally brought the disturbances to an end.

Sancho's account of the riots is contained in four letters to John Spink, all of which are reproduced on this page. The first is the longest and the most immediate, clearly written while the disturbances were taking place. Sancho ironically comments on the 'worse than Negro barbarity of the populace' while staying true to his ideals by declaring that 'I am for universal toleration'. In the later letters, he passes through a range of emotions, from fear, to outrage, to relief. I have retained eighteenth-century spellings in these letters and expanded Sancho's initialisation. For more information and analysis of this letter, see my article: Brycchan Carey, '"The worse than Negro barbarity of the populace": Ignatius Sancho witnesses the Gordon Riots', in The Gordon Riots and British Culture, ed Ian Haywood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2011), pp. 144–61. In this article, I argue that Sancho's supposed 'eye-witness' account of the Gordon Riots was more probably a literary construct, based on reading in the newspapers.

LETTER LXVII

To J[OHN] S[PINK], ESQ.

Charles Street, June 6, 1780.

DEAR AND MOST RESPECTED SIR,

In the midst of the most cruel and ridiculous confusion, I am now set down to give you a very imperfect sketch of the maddest people that the maddest times were ever plagued with.—The public prints have informed you (without doubt) of last Friday's transactions;—the insanity of L[or]d G[eorge] G[ordon] and the worse than Negro barbarity of the populace; - the burnings and devastations of each night you will also see in the prints:—This day, by consent, was set apart for the farther consideration of the wished—for repeal;—the people (who had their proper cue from his lordship) assembled by ten o'clock in the morning. - Lord N[orth], who had been up in council at home till four in the morning, got to the house before eleven, just a quarter of an hour before the associators reached Palace-yard:—but, I should tell you, in council there was a deputation from all parties;—the S[helburne] party were for prosecuting L[or]d G[eorge], and leaving him at large;—the At[torne]y G[enera]l laughed at the idea, and declared it was doing just nothing; - the M[inistr]y were for his expulsion, and so dropping him gently into insignificancy;—that was thought wrong, as he would still be industrious in mischief;—the R[ockingha]m party, I should suppose, you will think counselled best, which is, this day to expel him the house—commit him to the Tower—and then prosecute him at leisure—by which means he will lose the opportunity of getting a seat in the next parliament—and have decent leisure to repent him of the heavy evils he has occasioned.—There is at this present moment at least a hundred thousand poor, miserable, ragged rabble, from twelve to sixty years of age, with blue cockades in their hats—besides half as many women and children—all parading the streets—the bridge—the park—ready for any and every mischief.—Gracious God! what's the matter now? I was obliged to leave off—the shouts of the mob—the horrid clashing of swords—and the clutter of a multitude in swiftest motion—drew me to the door—when every one in the street was employed in shutting up shop.—It is now just five o'clock - the ballad—singers are exhausting their musical talents—with the downfall of Popery, S[andwic]h, and N[ort]h.—Lord S[andwic]h narrowly escaped with life about an hour since;—the mob seized his chariot going to the house, broke his glasses, and, in struggling to get his lordship out, they somehow have cut his face;—the guards flew to his assistance—the light-horse scowered the road, got his chariot, escorted him from the coffee-house, where he had fled for protection, to his carriage, and guarded him bleeding very fast home. This—this—is liberty! genuine British liberty!—This instant about two thousand liberty boys are swearing and swaggering by with large sticks—thus armed in hopes of meeting with the Irish chairmen and labourers—all the guards are out—and all the horse;—the poor fellows are just worn out for want of rest—having been on duty ever since Friday.—Thank heaven, it rains; may it increase, so as to send these deluded wretches safe to their homes, their families, and wives! About two this afternoon, a large party took it into their heads to visit the King and Queen, and entered the Park for that purpose—but found the guard too numerous to be forced, and after some useless attempts gave it up.—It is reported, the house will either be prorogued, or parliament dissolved, this evening—as it is in vain to think of attending any business while this anarchy lasts.

I cannot but felicitate you, my good friend, upon the happy distance you are placed from our scene of confusion.—May foul Discord and her cursed train never nearer approach your blessed abode! Tell Mrs. S[pink], her good heart would ach, did she see the anxiety, the woe, in the faces of mothers, wives, and sweethearts, each equally anxious for the object of their wishes, the beloved of their hearts. Mrs. Sancho and self both cordially join in love and gratitude, and every good wish—crowned with the peace of God, which passeth all understanding, &c.

I am, dear Sir,

Yours ever by inclination,

I

GN. SANCHO

Postscript

The Sardinian ambassador offered 500 guineas to the rabble, to save a painting of our Saviour from the flames, and 1000 guineas not to destroy an exceeding fine organ: the gentry told him, they would burn him if they could get at him, and destroyed the picture and organ directly.—I am not sorry I was born in Afric.—I shall tire you, I fear—and, if I cannot get a frank, make you pay dear for bad news.—There is about a thousand mad men, armed with clubs, bludgeons, and crows, just now set off for Newgate, to liberate, they say, their honest comrades.—I wish they do not some of them lose their lives of liberty before morning. It is thought by many who discern deeply, that there is more at the bottom of this business than merely the repeal of an act—which has as yet produced no bad consequences, and perhaps never might.—I am forced to own, that I am for universal toleration. Let us convert by our example, and conquer by our meekness and brotherly love!

Eight o'clock. Lord G[eorge] G[ordon] has this moment announced to my Lords the mob—that the act shall be repealed this evening:—upon this, they gave a hundred cheers—took the horses from his hackney—coach - and rolled him full jollily away:—they are huzzaing now ready to crack their throats

HUZZAH

I am forced to conclude for want of room—the remainder in our next.

LETTER LXVIII

To J[OHN] S[PINK], ESQ.

Charles Street, June 9, 1780

MY DEAR SIR,

Government is sunk in lethargic stupor—anarchy reigns—when I look back to the glorious time of a George II. and a Pitt's administration—my heart sinks at the bitter contrast. We may now say of England, as was heretofore said of Great Babylon—"the "beauty of the excellency of the Chaldees—is no more;"—the Fleet Prison, the Marshalsea, King's- Bench, both Compters, Clerkenwell, and Tothill Fields, with Newgate, are all slung open;— Newgate partly burned, and 300 felons from thence only let loose upon the world.—Lord M [ansfield]'s house in town suffered martyrdom; and his sweet box at Caen Wood escaped almost miraculously, for the mob had just arrived, and were beginning with it—when a strong detachment from the guards and light-horse came most critically to its rescue—the library, and, what is of more consequence, papers and deeds of vast value, were all cruelly consumed in the flames.—Ld. N[orth]'s house was attacked; but they had previous notice, and were ready for them. The Bank, the Treasury, and thirty of the chief noblemen's houses, are doomed to suffer by the insurgents.—There were six of the rioters killed at Ld M [ansfield]'s; and, what is remarkable, a daring chap escaped from Newgate, condemned to die this day, was the most active in mischief at Ld. M[ansfield]'s, and was the first person shot by the soldier; so he found death a few hours sooner than if he had not been released.—The ministry have tried lenity, and have experienced tis inutility; and martial law is this night to be declared.—If any body of people above ten in number are seen together, and refuse to disperse, they are to be fired at without any further ceremony—so we expect terrible work before morning;—the insurgents visited the Tower, but it would not do—they had better luck in the Artillery-ground, where they found and took to their use 500 stand of arms; a great error in city politics, not to have secured them first.—It is wonderful to hear the execrable nonsense that is industriously circulated amongst the credulous mob—who are told his M[ajest]y regularly goes to mass at Ld. P[et]re's chaple—and they believe it, and that he pays out of his privy purse Peter-pence to Rome. Such is the temper of the times—from too relaxed a government;—and a King and Queen on the throne who possess every virtue. May God in his mercy grant that the present scourge may operate to our repentance and amendment! that it may produce the fruits of better thinking, better doing, and in the end make us a wife, virtuous, and happy people!—I am, dear Sir, truly Mrs. S[pink]'s and your most grateful and obliged friend and servant,

I. SANCHO.

The remainder in our next.

Half past nine o'clock.

King's-Bench prison is now in flames, and the prisoners at large; two fires in Holborn now burning.

LETTER LXIX

June 9, 1780

DEAR SIR,

Happily for us the tumult begins to subside—last night much was threatened, but nothing done—except in the early part of the evening, when about fourscore or an hundred of the reformers got decently knocked on the head;—they were half killed by Mr. Langdale's spirits—so fell an easy conquest to the bayonet and but-end.—There is about fifty taken prisoners—and not a blue cockade to be seen:—the streets once more wear the face of peace—and men seem once more to resume their accustomed employments;—the greatest losses have fallen upon the great distiller near Holborn-bridge, and Lord M[ansfield]; the former, alas! has lost his whole fortune;—the latter, the greatest and best collection of manuscript writings, with one of the finest libraries in the kingdom.—Shall we call it a judgement?—or what shall we call it? The thunder of their vengeance has fallen upon gin and law—the two most inflammatory things in the Christian world.—We have a Coxheath and Warley of our own; Hyde Park has a grand encampment, with artillery, Park, &c. &c. St. James's Park has ditto—upon a smaller scale. The Parks, and our West end of the town, exhibit the features of French government. This minute, thank God! this moment Lord G. G. is taken. Sir F. Molineux has him safe at the horse-guards. Bravo! he is now going in state in an old hackney-coach, escorted by a regiment of militia and troop of light horse to his apartments in the Tower.

Off with his head—so much—for Buckingham.We have taken this day numbers of the poor wretches, in so much we know not where to place them. Blessed be the Lord! we trust this affair is pretty well concluded.—If any thing transpires worth your notice—you shall hear from

Your much obliged, &c. &c.

I. SANCHO.

Best regards attend Mrs. S[pink]; his lordship was taken at five o'clock this evening— betts run fifteen to five Lord G[eorge] G[ordon] is hanged in eight days:—he wished much to speak to his Majesty on Wednesday, but was of course refused.

LETTER LXX

To J[OHN] S[PINK], ESQ.

June 13, 1780

MY DEAR SIR,

That my poor endeavours have given you information or amusement, gratifies the warm wish of my heart;—for as I know not the man to whose kindness I am so much indebted—I may safely say, I know not the man whose esteem I more ardently covet and honour.—We are exceeding sorry to hear of Mrs. S[pink]'s indisposition, and hope, ere this reaches you, she will be well, or greatly mended.—The spring with us has been very sickly—and the summer has brought with it sick times— sickness! cruel sickness! triumphs through every part of the constitution:—the state is sick—the church (God preserve it!) is sick—the law, navy, army, all sick—the people at large are sick with taxes—the Ministry with Opposition, and Opposition with disappointment.—Since my last, the temerity of the mob has gradually subsided;—numbers of the unfortunate rogues have been taken:—yesterday about thirty were killed in and about Smithfield, and two soldiers were killed in the affray.—There is no certainty yet as to the number of houses burnt and gutted—for every day adds to the account—which is a proof how industrious they were in their short reign.—Few evils but are productive of some good in the end:—the suspicious turbulence of the times united the royal brothers;—the two Dukes, dropping all past resentments, made a filial tender of their services:—his Majesty, God bless him! as readily accepted it—and on Thursday last the brothers met—they are now a triple cord—God grant a blessing to the union! There is a report current this day, that the mob of York city have rose, and let 3000 French prisoners out of York-castle—but it meets with very little credit.—I do not believe they have any thing like the number of French in those parts—as I am informed the prisoners are sent more to the western inland counties—but every hour has its fresh cargo of lies. The camp in St. James's Park is daily increasing—that and Hyde Park will be continued all summer.—The K[in]g is much among them them—walking the lines—and examining the posts—he looks exceeding grave. Crowns, alas! have more thorns than roses.

You see things, my dear Sir, with the faithful eye which looks through nature—up to nature's God—the sacred page is your support—the word of God your shield and armour— well may you be able so sweetly to deduce good out of evil—the Lord ordereth your goings—and gives the blessing of increase to all your wishes. For your kind anxiety about me and family, we bless and thank you.—I own, at first I felt uneasy sensations—but a little reflection brought me to myself.—Put thy trust in God, quoth I.—Mrs. Sancho, whose virtues outnumber my vices (and I have enough for any one mortal) feared for me and for her children more than for herself.—She prayed too, I dare say—and her prayers were heard. America seems to be quite lost or forgot amongst us;—the fleet is but a secondary affair.—Pray God send us some good news, to chear our drooping apprensions, and to enable me to send you pleasanter accounts;—for trust me, my worthy friend, grief, sorrow, devastation, blood, and slaughter, are totally foreign to the taste and affection of

Your faithful friend

and obliged servant,

I

. SANCHO.

Our joint best wishes to Mrs. S[pink], self, and family.

About this extract

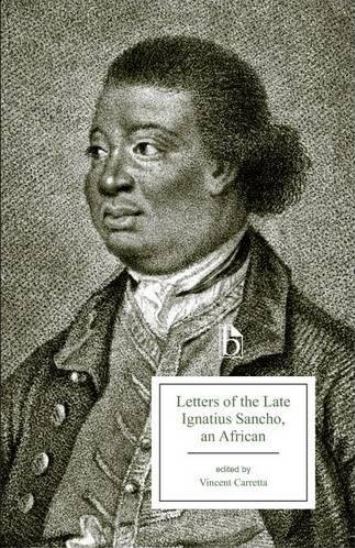

Sancho's letters about the Gordon Riots first appeared in The Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African, published in 1782.

Sancho's Letters was published in five different editions between 1782 and 1803 before going out of print until the 1960s. The book is now available in several editions, including a paperback edition with notes and an introduction, edited by Vincent Carretta and available from: